In the last decade, board games have enjoyed a resurgence in popularity, with the old classics of Monopoly, Scrabble, and Sorry! giving way to innovative modern classics like Pandemic, 7 Wonders, Agricola, and King of Tokyo.

Many of these games are a good deal more complex than the games of yesterday, with detailed player figures, tokens, cards, boards, and more. Consequently, manufacturing costs are rising; it’s not unusual for board games to cost more than $50 or even $100.

For those undertaking the challenging task of creating a new board game, it’s more necessary than ever to prevent competitors from potentially undercutting you by creating a stripped down, lower-cost derivative that emulates the creative elements of your game. While trademarks and copyrights can protect your game’s name, artwork, and marketing materials, how can you prevent someone from emulating the play style of your game?

Many people don’t realize that board games can actually be patented.

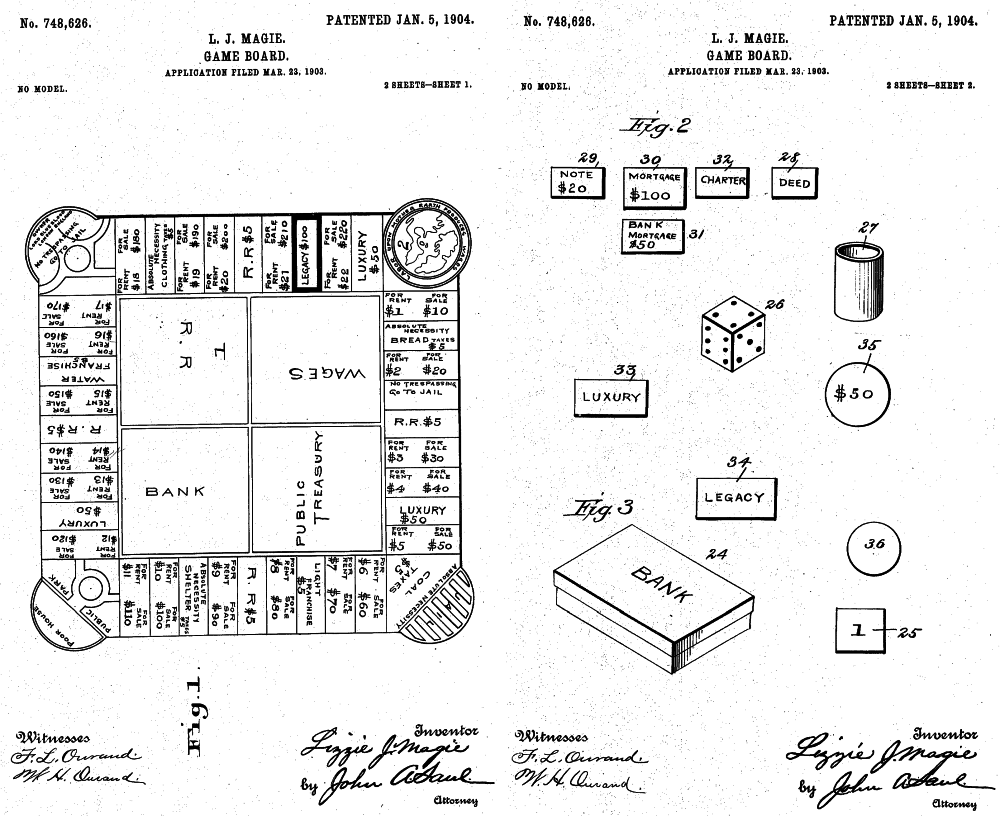

While many associate patents with manufactured devices, the U.S Patent & Trademark Office also grants patents for detailed processes. Thus, board games and card games and the rule sets that govern them have long been eligible for patent protection. In fact, there are board game patents dating back more than a century. For instance, Patent No. 748,626 was granted to Lizzie J. Magie in 1904, for a creation titled “Game-Board.” Magie describes the game thusly:

My invention, which I have designated ‘The landlord’s game,’ relates to game-boards, and more particularly to games of chance. The object of the game is to obtain as much wealth or money as possible, the player having the greatest amount of wealth at the end of the game after a certain predetermined number of circuits of the board have been made being the winner.

A glance at the drawings included in the patent application make it immediately obvious that Magie’s The Landlord’s Game is in fact the game that, with some modifications, was published under the name Monopoly (years after Magie’s patent expired and her work was ‘borrowed’).

The man who built on Magie’s idea, Charles Darrow, was issued Patent No. 2,026,082 in 1935 for the game modern audiences recognize as Monopoly. Since then, many popular board and card games have been patented. A few recognizable examples include:

- Apples to Apples – No. 6,328,308

- Battleship – No. 1,988,301

- Magic: The Gathering – No. 5,662,332

- Perfection – No. 3,710,455

There is clearly a long history of patents being granted for games. So, what does a modern game developer need to know when it comes to patenting a board game?

Obtaining a patent for a modern board game based strictly on a mode of play is more difficult than it used to be.

It’s highly likely that some of the patents previously granted for board games would not have been awarded under the USPTO’s current standards. For instance, consider the recent case of Ex parte Kuester, in which Deitra and Eric Kuester appealed and failed to overturn a rejection of claims for a game involving:

…arranging a plurality of cards on a base to indicate a path of movement, wherein said base comprises a plurality of compartments, sized and shaped to receive and retain each card in place for the duration of a game… playing a game on said base in accordance with predetermined rules… retaining each card in place for the duration of the game… wherein a game piece is advanced along said path of movement…

The Kuesters’ game had a base imprinted with a series of sockets—perhaps arranged in a grid—into which players could place cards, building a board across which characters moved their pieces. While this sounds fairly unique, the problem is that 2014’s Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International ruling created a precedent which indicated that organizing an abstract concept into a set of rules—whether for a board game or a computer program—is not patentable. The Appeals Court found that the Kuesters’ game was merely a set of organized rules, thus falling under the Alice precedent.

While the use of a base in combination with cards to create a dynamic game board might strike some as being a unique and patent-worthy innovation, the Ex parte quotes the examiner’s original rejection, in which they indicate that the cards and base combination:

…do not actually perform the step of arranging a plurality of cards, or of playing the game, and since the method could be performed with common game playing items (e.g. a deck of cards and a table) this is not considered the use of a particular machine to perform any step of the claimed method, nor is it a meaningful tie to a machine or apparatus.

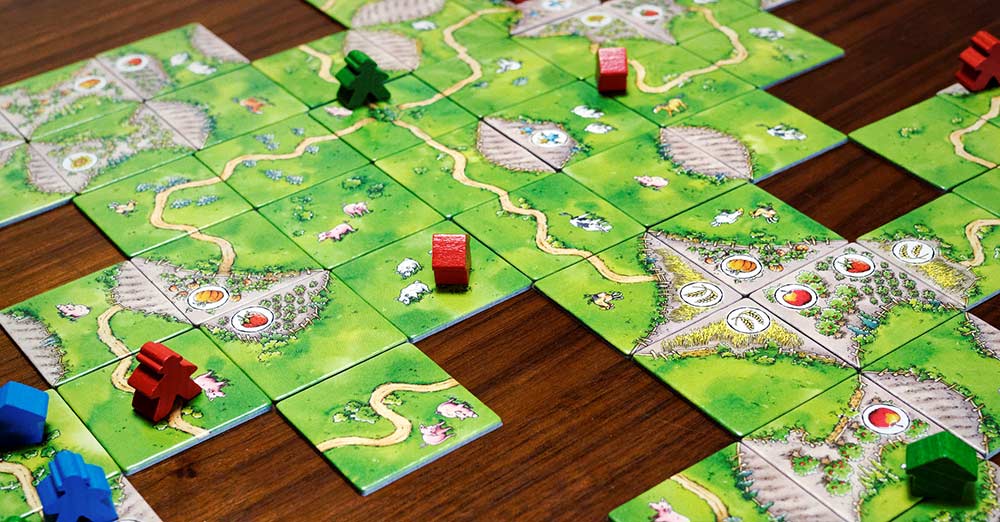

One of the most popular games released in the last 20 years is Carcassonne, a game in which players arrange cards to build a game board. Thus, the examiner’s observations suggest that they had a decent understanding of the current state of the board game industry.

The takeaway from the Kuesters’ failure to obtain a patent is that a patentable game must be exceptionally unique with regard to its rules or form (preferably both) for it to be successfully patented.

What are examples of known games that would pass muster with the Patent Office, even today?

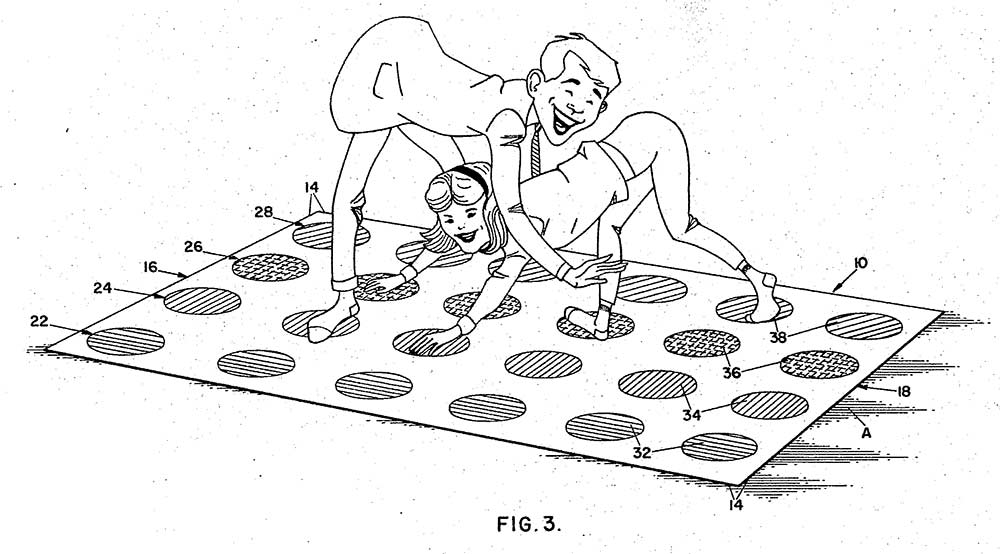

Let’s examine two children’s games: KerPlunk and Twister. These games date back many decades, but still demonstrate innovations that would likely be worthy of a patent in the modern day.

Twister is the simpler of these games. There are two game elements, a large mat with a grid of colored circles, and a specially designed spinner indicating a combination of color and left/right hand/foot. Each time the spinner is spun, players place the indicated limb on an open circle of that color. As players lose their balance and allow an elbow or knee to touch the mat, they are eliminated, with the winner being the last player to remain upright.

While Twister’s rules and nature of play are extremely simple, they are exceptionally nonobvious. There is no tabletop gameboard, cards, or even dice. Just a very large color-coded plastic mat, and a specially designed spinner that compels players to physically interact with the mat. Twister is not a modification of any existing game, commercial or otherwise, and its rules are intrinsically tied to the form and function of the game’s elements. Thus, it would be very patentable now, as was the case in 1966 when Patent No. 3,454,279 was granted for Twister.

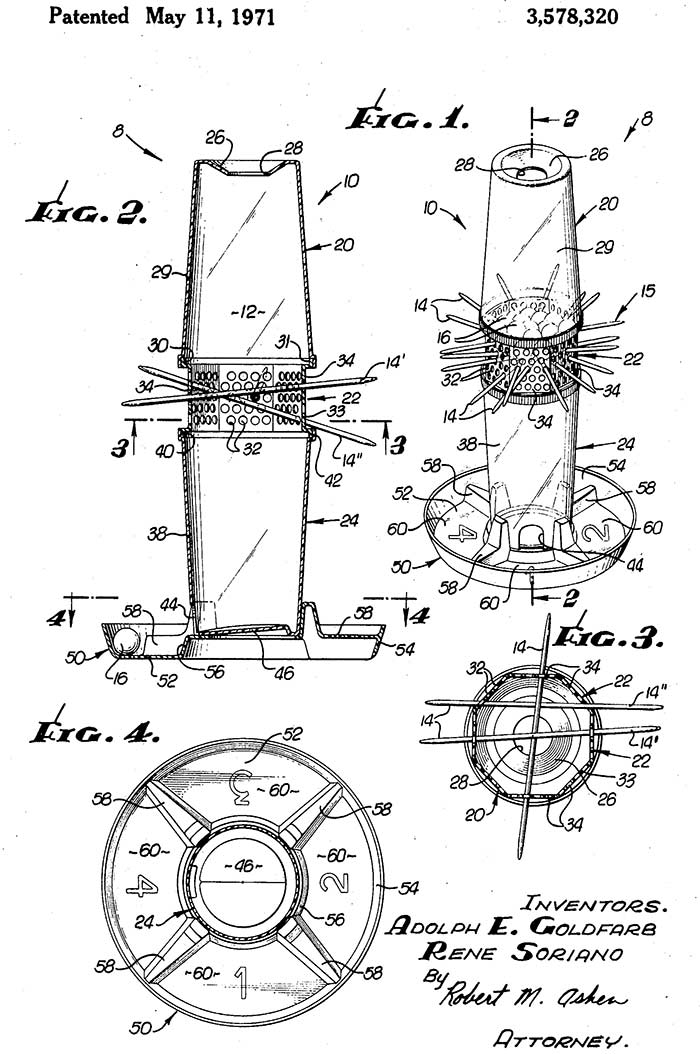

KerPlunk, another game marketed to children, involves a plastic tube into which dozens of plastic sticks are inserted through holes in the cylinder’s middle, creating a ‘nest’ onto which a handful of marbles are placed. At the start of each turn, the tube is rotated so that an output chute at the bottom points into the section of a divided catch basin corresponding to the current player. The player then removes a single stick, with the goal of not dropping any of the marbles. After all the marbles have dropped, the game is over, and the player with the fewest marbles in their tray wins.

The gameplay of KerPlunk is built around how players interact with a specially designed physical device. While it’s possible to perceive the influences of games of dexterity like Pick-Up Sticks and Jenga, the plastic frame into which the sticks and marbles are placed is a unique and complex device, and indispensable to gameplay and even scorekeeping. Thus, it’s unsurprising that Patent No. 3,578,320 was granted for KerPlunk in 1968.

Developing a unique device that is intrinsic to the game rules designed around it is an excellent means of clearing the patentability hurdles put in place by Alice and other restrictive rulings. You have not only created a game that is patentable, but a separate physical device that is also patentable.

Another consideration when developing your game is whether there are obvious alternative modes of play. Look at the house rules that have become popular with Monopoly (e.g. collecting all fees paid by players in the center of the board, and awarding them to whoever lands on 'Free Parking'), or the Legacy versions of Risk and Pandemic, which introduce permanent modifications to game boards, characters, and even rules as a consequence of player actions. If you can identify ways in which your game can be stripped down or modified into new play styles, including these variations as claims can help to protect your game from those who would circumvent your patents.

I strongly advise that game designers engage with me early in the design process. This provides opportunities to develop ideas and introduce concepts to make the game more patentable. The barrier to patentability is high these days, but it can be overcome. For more assistance with patenting your game, contact the Law Office of Michael O’Brien by calling (916) 760-8265, or sending us a message using our contact form.