When it comes to commercial marketing applications, Rule #1 has long been: Don’t use works you don’t own, unless you have a license. Whether it’s photographs, video, music, or types of creative work, you need to secure a proper license first.

However, a ruling handed down in June of 2018 could potentially upend that common-sense approach when it comes to the Web.

A photographer who sued a website operator for using one of his photos without permission was hit with a decidedly disappointing court ruling.

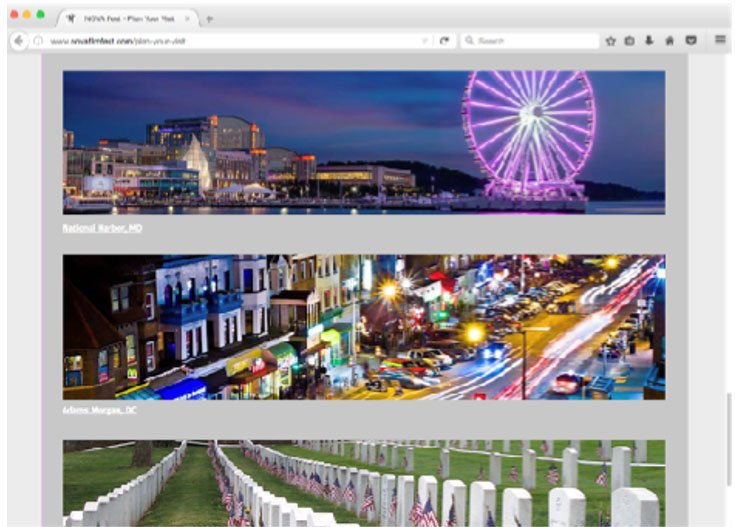

Photographer Russell Brammer travels across the country, taking photos for weddings and portraits, as well as photojournalism and general interest pieces. In 2011, Brammer took a time-lapse photo of Adams Morgan, a vibrant commercial and residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C. Brammer registered the photo with the U.S. Copyright Office in 2016, and was granted a copyright the following year.

That same year, the owner of Violent Hues Productions, a video productions service, came across Brammer’s photo online. The company’s owner, Fernando Mico, stated that there was no indication that the photo was copyrighted, and he believed it to be free to use. He posted the photo on the website for the Northern Virginia Film Festival, an event he organizes.

In 2017, Brammer discovered Mico’s use of the photo, and sent a cease and desist letter to Violent Hues, after which the photo was immediately removed.

Brammer subsequently filed two claims against Violent Hues, alleging that the company had committed copyright infringement, and had removed copyright information from the photo, replacing it with a false claim of copyright. Violent Hues, in turn, argued for a summary judgment in their favor, on the basis of fair use.

The court ultimately found that Violent Hues’ used of Brammer’s photo fell under fair use.

The judge presiding over the case, Claude M. Hilton, examined the claim of fair use based upon a four-factor test, as cited in Bouchat v. Baltimore Ravens:

1. The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature.

Two questions are raised by this point: whether the new use of the work is ‘transformative,’ and the extent to which that use is commercial in nature. Hilton found that while Brammer’s original intent was promotional and expressive in nature, Violent Hues used the photo to inform their customers, by providing festival attendees with information about the local area.

Hilton also held that the use was non-commercial, as the photo was not used to advertise a product or directly generate revenue. Lastly, he found that the use was in good faith, based upon Mico’s claim that he found no indication that the photo was copyrighted, and that he removed the photo from his site at Brammer’s request.

2. The nature of the copyrighted work.

With regard to the question of the nature of the work, Hilton referred to A.V. ex rel. Vanderhye v. iParadigns, LLC., in which the court’s findings stated that, while “a use is less likely to be deemed fair when the copyrighted work is a creative product… if the disputed use of the copyrighted work ‘is not related to its mode of expression but rather to its historical facts,’ then the creative nature of the work is mitigated.”

Because Branner’s photo was a “factual depiction of a real-world location,” and that Violent Hues “used the photo purely for its factual content,” Judge Hilton found that Violent Hues’ use of the photo met the second requirement for fair use.

Hilton also pointed out that Brammer had published the photo on several websites as far back as 2012, and that at least one of these postings did not include copyright information.

3. The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.

Judge Hilton pointed out that Violent Hues cropped roughly half of the photo, using “no more of the photo than was necessary to convey the photo’s factual content.” Thus, he found that Violent Hues had satisfied the third factor.

4. The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Lastly, Hilton stated that there was no evidence that “Violent Hues’ use of the photo had any effect on the potential market for the photo.” As evidence, he cited the fact that Brammer had been financially compensated for the photo six times, with two of these sales occurring after Violent Hues posted the image on their site. Judge Hilton also pointed to testimony by Brammer, in which the photographer apparently “testified that he currently makes no effort to market the photo.”

Consequently, Brammer found that this last factor was fulfilled, and thus Violent Hues’ use of the photo was not copyright infringement, as it fell under fair use.

In my opinion, Judge Hilton missed the mark, and the ruling will almost certainly be overturned in appeals, in the photographer’s favor.

I frequently tell clients, “Everyone thinks everything is fair use—especially in the age of Google—but fair use is rare in commercial settings.” Violent Hues use of Brammer’s photo is not one of these rare cases.

Here’s why.

1. Violent Hues used the plaintiff’s photo in an advertisement to persuade people to spend money on a for-profit event.

Judge Hilton stated that Violent Hues’ use of the photo was non-commercial, as it was used strictly to ’inform’ festival attendees about the local area. However, the photo was prominently used on a website designed for a single purpose: to promote a revenue generating event.

While an archival version of the site Northern Virginia Film Festival isn’t available, a blog post on the case published by photography blogger PetaPixel provides a low-resolution screenshot of the page on which the photo appeared.

While the photo was significantly cropped, it’s clear that the photo is being used in a manner emphasizing its artistic merit, rather than in a strictly practical, explanatory capacity. This doesn’t comply with the standard fair use.

Judge Hilton’s argument that the cropping of the photo was done to hone in on the practical information contained in the photo seems facile in light of the fact that all of the photos visible in the screenshot feature the same cropping.

2. The argument that Brammer’s work is more factual than artistic is inherently flawed.

Let’s say that you dropped your phone and it accidentally took a photo of your shoe. That’s a factual work, one produced by virtue of an event, without any human intent.

In an artistic photo, you compose the shot. You adjust the timing, light, and angle, with the subject in mind, to create an image. This is an inherently artistic creation.

3. The fact that Brammer sold the photo both before and after the infringement is not sufficient to argue that the market was not impacted by Violent Hue’s actions.

The court seems to have been operating under the belief that, since the plaintiff sold copies of the work both prior and subsequent to the infringement, that the market for the work was not diminished.

The factor that Judge Hilton was examining here, whether the unpermitted use of the work impacted the potential market for or value of the work, exists specifically in order to block arguments for piracy being fair use. If you make pirated copies of a piece of software and distribute them on a torrent site, this factor shoots down any argument of fair use.

However, the inverse situation does not automatically mean that the use falls under fair use. Brammer put forth evidence that there was a market for their work, and that it was affected. That’s all you need at the summary judgment stage. How much it was affected, and thus the amount of damages to be considered, is an issue for a jury to decide. In this case, the judge made a premature value judgment.

Brammer’s lawsuit includes a number of mistakes that undermine his efforts to protect his work, which should serve as important lessons to other rightsholders.

While the ruling against Brammer will likely be overturned, he made several mistakes, both during and prior to the lawsuit.

Part of the reason the case was dismissed via summary judgment was because his lawyer did not include a declaration to oppose such a motion. Such a filing should also have included important statements of fact that would have helped to prevent the summary judgment.

Another key issue is that there is no mention of what damages are being requested by Brammer, and what the basis is for the damages. It would have been very easy to have Brammer make a declaration that includes this information, along with material information as to how the market has been affected.

What else can be learned from this case?

First, file a copyright application within a few weeks of publishing a work. Brammer waited 5 years, during which time he published his photo on numerous sites. While copyright exists from the moment a work is fixed in a tangible format, you can’t claim damages for infringement occurring prior to registering a work with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Secondly, don’t use the works of others without permission. This case is garnering a great deal of attention because the ruling was so unexpected. Typically, such a defendant would lose their case right off the bat. In commercial applications, particularly those involving marketing, there are very few contexts in which fair use comes into play.

This brings us to the last point. Fair use is a defense, but not a great one. In this case, both parties made it all the way to summary judgment, and will have to front the costs of dealing with appeals. Violent Hues is going to spend a lot of money, and if Brammer continues to pursue this—and given how critical this case is when it comes to the concept of copyright as a whole, someone or other will likely provide assistance—Violent Hues will spend a lot of money to ultimately lose this case.

Hiring an intellectual property attorney from the get-go can help save a lot of angst—and money—in the long run. The Law Office of Michael O’Brien can help. To learn more, contact us by calling (916) 760-8265, or sending us a message using our contact form.